As COVID rates rise in Europe and Asia, how worried should Americans be about another wave? – USA TODAY

- We’re in a “messy” part of the pandemic, according to infectious disease experts.

- Trends in other countries and in our own wastewater offer clues on if another COVID surge is on the way.

- Experts say it may be politically and socially impossible to get ahead of another surge.

Five times in the last two years coronavirus cases spiked in Europe a few weeks before they climbed in the United States.

Now, cases are rising again in at least a dozen European countries from Finland to Greece. And they’re skyrocketing in South Korea, Hong Kong and parts of mainland China.

Experts here worry some of these countries may be predicting our future.

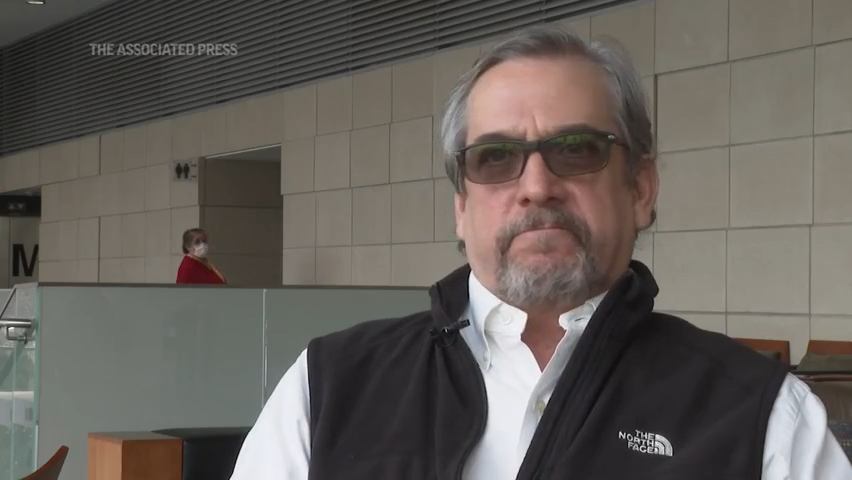

“We’re learning a lot about the next wave that’s going to happen in the U.S.,” said Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, California. “It’s going to happen. It’s unavoidable.”

Researchers say they’re not yet sure if the United States is heading for another tsunami of cases or just a bit of a bump.

“It’s going to be a surge of some kind, the magnitude of which is unclear,” Topol said.

Predictive models can indicate that a wave of infections is coming, but can’t accurately tell how big that wave will be, said Dr. Joshua Schiffer, an infectious disease expert at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, who specializes in developing mathematical models of disease.

That’s because so much of an outbreak is determined by how people respond. “The answer to this question goes well beyond what we can explain with science,” he said.

The best way to describe the moment we’re in now in the pandemic, Schiffer said, is “messy.”

“Everyone knew the offramp from the pandemic would be very bumpy and unpredictable,” Schiffer added. “I’m not even totally sure we’re on the offramp yet.”

Around the world, infections are largely due to the BA.2 version of omicron, which arrived in the U.S. late last year and has been growing slowly since, now accounting for about a quarter of cases here, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As a percentage of cases, BA.2 has roughly doubled each week for the last month, suggesting it’s poised to become dominant.

That’s what happened in the United Kingdom, which had as bad an omicron wave as the U.S. did not long ago and is now enduring a second hit from BA.2.

“That indicates that maybe the virus is getting a foothold, but it’s a little hard to tell right now,” said Jeffrey Shaman, director of the Climate and Health Program at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. “Because the U.K. is ahead of us on this, it provides sort of an analogy that we can work from.”

In addition to data from other countries, one other potential advance indicator also is suggesting cases in U.S. cases may be about to rise again. Analysis of coronavirus particles in wastewater – which climbs even before people know they’re infected – shows increases in 40% of communities after weeks of national decline. According to the CDC, more than a quarter of the 400 tracked sites have seen at least a doubling of viral particles in the last two weeks and 53 have seen a 1,000% jump.

The wastewater data isn’t definitive and some, including Rob Knight, a professor at the University of California, San Diego who tracks sewage on campus and in the surrounding communities, are not convinced the data is even accurate.

But Shaman said, “it’s one more piece of information that’s pointing towards being prudent, being cautious.”

William Hanage, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said he can’t guess how bad another wave will get, but he knows where it’s likely to hit hardest.

“The only thing I’m very prepared to predict is that places with large quantities of unboosted, unvaccinated older folks are going to have a more consequential experience with BA.2,” he said.

What the worldwide trends suggest for the US

COVID-19 spikes in Asian countries such as South Korea and China also are coming after two years of very successful prevention efforts.

Although their populations are highly vaccinated, the shots most common in Hong Kong, for instance, are not as effective as the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna shots used in the U.S., Hanage said. And very few people there have protection from natural infection.

Omicron is so much more contagious, he said, that it’s been impossible to contain infections using the strategies that worked in Asian countries earlier in the pandemic. With previous variants, 2 out of 3 infections needed to be stopped to slow the spread. But with BA.2, 7 out of 8 must be stopped, he said, “which is much harder to do.”

Hong Kong is particularly “unique and terribly sad,” Schiffer said, because the elderly population there remains undervaccinated, so older people are dying at similar rates as seen in the earliest days of the pandemic in places like Wuhan, China, parts of Italy, and New York City.

Mainland China is another wild card, Topol said. With infections spiking there, it could spur the development of another variant, or simply keep the current one in circulation long enough to reinfect people around the world as their immunity fades over time.

It remains to be seen, Topol said, how long the immunity Americans have built up over two years of vaccinations and infections, will last in the face of the highly contagious BA.2.

Compared to Asia, the current situation in Europe is more similar to ours – and therefore more predictive of our future, the experts said. As here, most of Europe recently lifted mask mandates and other social distancing requirements. BA.2 is gaining ground or is already dominant across Europe.

And as with Americans, many people are vaccinated or have been infected over the last two years, Schiffer said.

But Europe is not the same as the United States.

“There are a number of things which tug the U.S. experience away from the European one,” Hanage said.

Vaccination and booster rates in many European countries are higher than in the U.S., so most of the infections in places like Denmark have been mild, Hanage said.

“It’s not altogether clear,” Hanage said, why BA.2 hasn’t made more inroads in the United States, because it appears to be about 20% more infectious than BA.1.

The U.K. is really the country to keep an eye on to get a sense of how bad a new surge might be, Shaman said. It had a recent BA.1 outbreak like ours and is closest physically to the U.S.

“The thing that I think we need to watch is to see really what happens there – whether or not this takes off or it plateaus or just flames out,” he said. “Because that may give us some sense here in the U.S. as to whether or not the boosting and the recent wave of omicron BA.1 is still conferring protection against BA.2.”

What to do about another surge

There’s no question it’s easier to stop a surge that’s just beginning than one that’s taken hold, Shaman said.

“The earlier you intervene to short circuit or disrupt that exponential growth or at least lower it, the better off you are, the more you’ll flatten the curve,” he said.

But it may be politically and socially impossible to get ahead of this one, Shaman said, because Americans are so sick of restrictions and mandates.

Earlier this week, Congress declined to support additional funding for President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 prevention measures, which would provide money for testing, treatments, boosters and development of next-generation vaccines, among other things.

The main way to stop coronavirus cases remains the same, Hanage said: get vaccinated, and particularly if you’re a senior citizen, boosted. Boosting will have the biggest effect for people over 65, he said, because they are most vulnerable to severe outcomes after catching COVID-19.

Those who are healthy and fully vaccinated and boosted or recently infected are probably well protected at the moment, Hanage said. But omicron remains highly contagious and “it’s not going away anytime soon – unless something else comes along and displaces it, which I wouldn’t rule out.”

Topol said he’d like to see the federal government make a big booster push, allowing fourth shots for people who want them and encouraging vaccinations for those who are relying on past infections to protect them.

And though each individual decision to wear a mask may not do much to stop the pandemic, Schiffer said, the combination of many people wearing them – particularly indoors at potentially super-spreader events – could make a dramatic difference, especially at a time like this, when cases seem to be just beginning to rise.

“It is an incredibly effective tool if used at scale and importantly, if people use the best mask possible,” Schiffer said, adding that he understands that it’s not a simple issue to ask people to don masks again so soon.

America has paid the price before of not paying attention to early warning signs, such as cases in Europe and rising wastewater levels. Topol said he doesn’t see any indication that we’ve learned from those past mistakes.

“Who isn’t sick of (the pandemic)? Who doesn’t want this to be over once and for all?” he said. But “you can’t ignore the signals. They’re unequivocal.”

Contributing: Adrianna Rodriguez

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

Some COVID survivors are suffering from PTSD

PTSD is commonly associated with veterans of military combat, but it can occur after exposure to other violent, dangerous or frightening events. And now the CDC lists it as an effect of COVID-19 illness or hospitalization. (March 17)

AP